Beautiful Thinking.

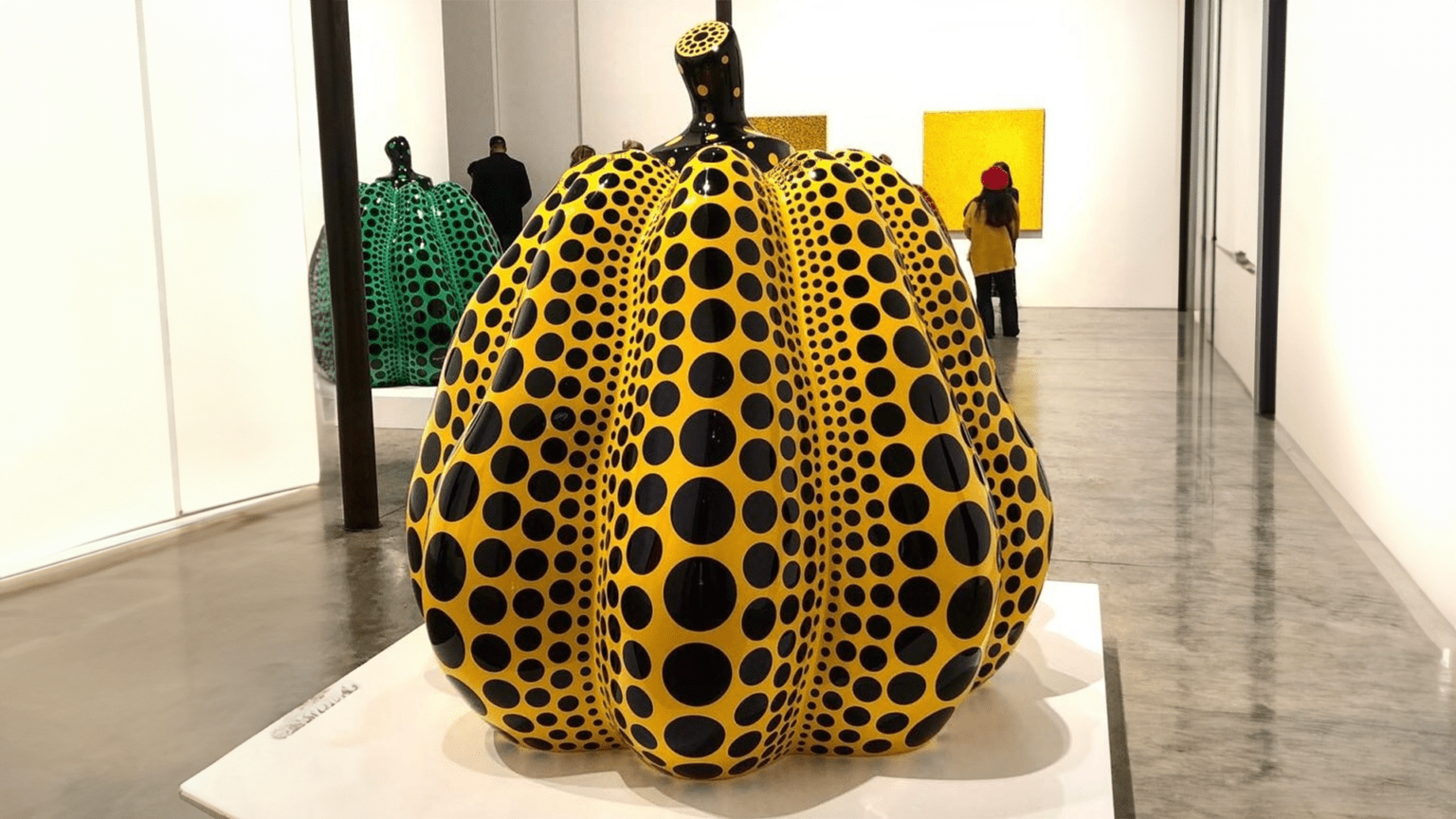

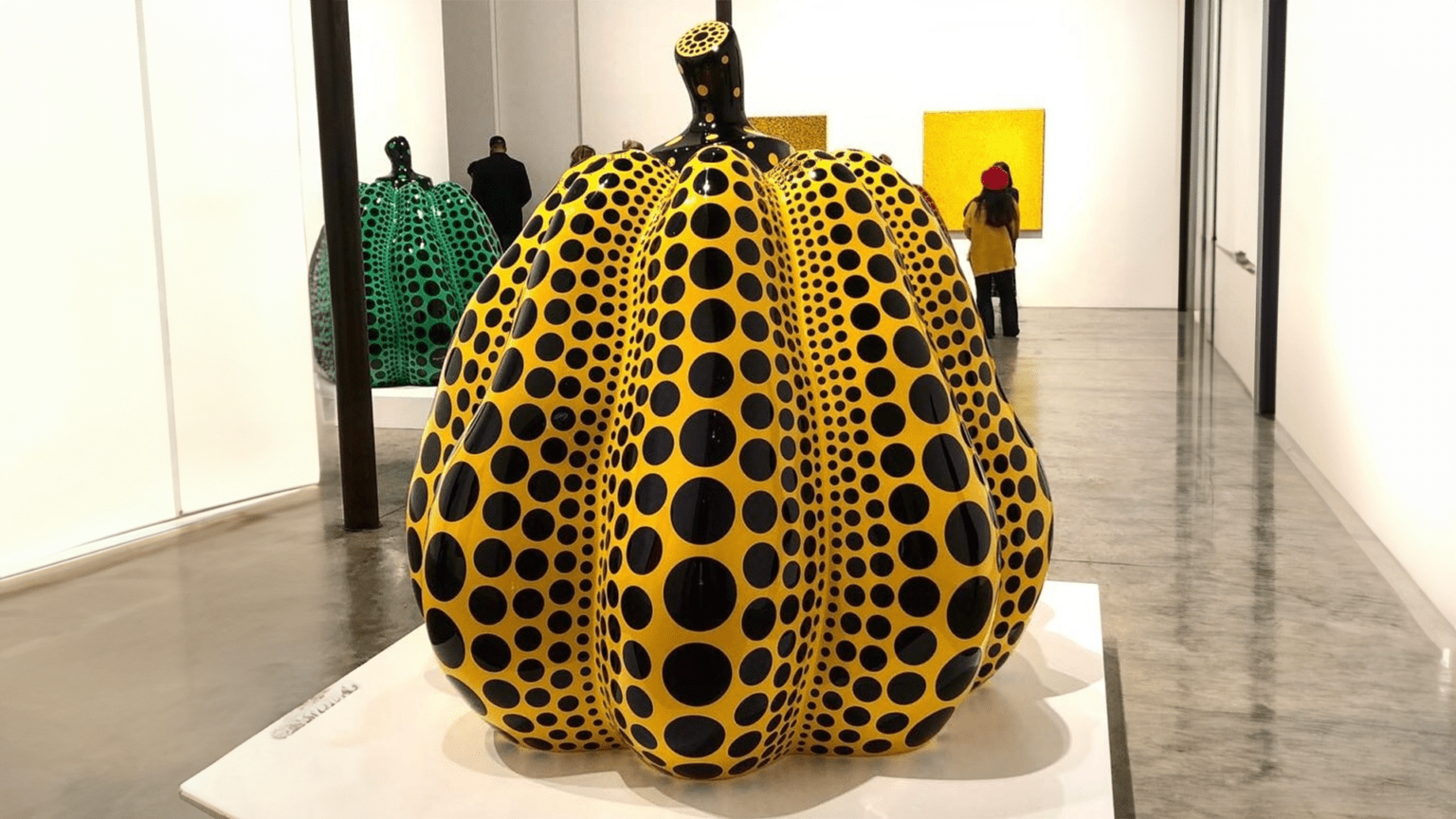

After first seeing her work IRL at the Victoria Miro exhibition in 2018 – a gallery which has played home to her work in thirteen exhibitions to date – Emily became obsessed. It was here that she experienced first hand the impact of Kusama’s famed pumpkins.

Her dedication to her art, for which she is instantly recognisable, is a testament to any and all creative who undertakes their work to free their mind, even when the world fails to recognise their significance. When diving into the decades of her career, it is clear that Kusama often found the cruel world too much to bear, and her art has been her saviour.

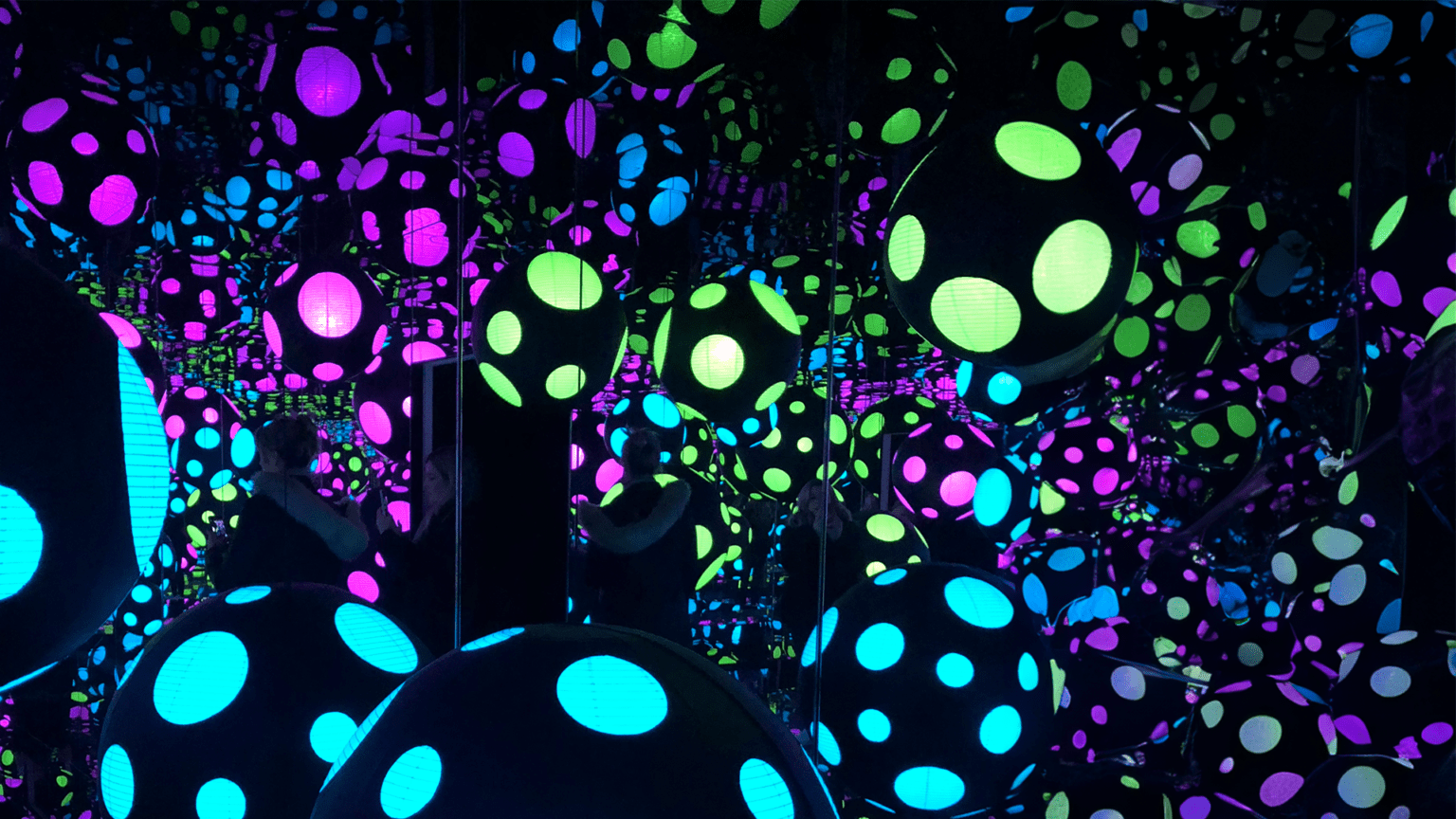

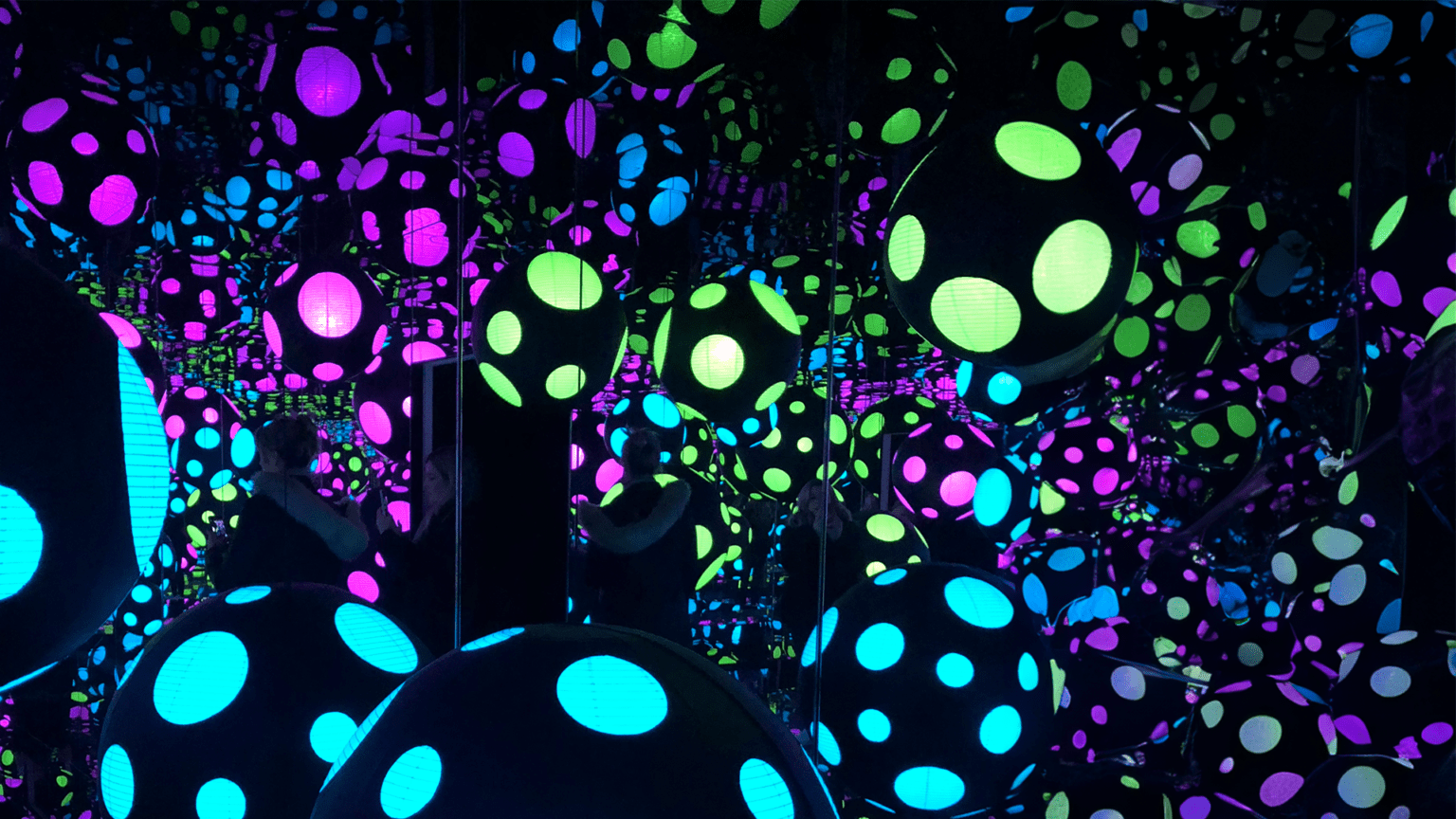

In a world today where the currency of success lies in an ability to go viral, Kusama has provided immersive experiences which are fodder for the Instagram masses, her infinity room installations to name but one. But fans who have followed her career over decades understand that her art is borne of a desire to free her mind, carrying her through periods of immense struggle in her mental health. Since 1977, Kusama has lived – by choice – in a mental health facility, after she met a doctor at the facility using art therapy to treat mental illness. Her studio is based a few minutes walk from her chosen home.

What is also a credit to her work and its popularity today, is Kusama’s ability to dissect human nature and bring it to life in fantastical and thought-provoking ways. When interviewed on these installations which have become global phenomena, she highlighted the ultimate vanity of indulging in the endless reflection of one’s self. Whilst aiming to evoke a sense of individuality amongst the masses of humanity, “like one little polka dot, among millions of other celestial bodies”. There is a sense of irony that the exhibitions result in people queuing for hours to take a selfie in the space over a matter of seconds.

Emily shared that her experience of Kusama’s infinity room at London’s Tate Museum last year, “felt like a magical transportation to another world.” It was also in this exhibition that she was struck with the poignancy of images of Kusama over the decades of her illustrious, and at times, fractured career.

Following a challenging childhood amongst a fractured family unit, Kusama found herself experiencing vivid hallucinations at just 10 years old. She described them as “flashes of light, auras or dense fields of dots”. By painting these hallucinations, she sought to give them a footing in reality and tackle the strain they put on her life.

Polka dots are an integral component in Kusama’s work, borne of her hallucinations and symbolising her fears and struggles with sexual phobias and men, fuelled by her father’s infidelities which in turn, triggered her mother’s violent tendencies. Her mother was also passionate about preventing Kusama from indulging in her artistic talents during her childhood. After joining Kyoto Municipal School of Arts and Crafts in 1952, Kusama made the significant move to New York, in her desire to leave Japan and its antiquated and contemptuous view of women.

It was in New York however she discovered that the lack of respect for the work of women persisted. Whilst she formed working and close relationships with respected artists such as Donald Judd – who lived in the same Greenwich Village loft as Kusama – and Joseph Cornell, her work was consistently overshadowed by her male peers.

Following her solo exhibition, ‘One Thousand Boats’, in which she plastered repeating images across the walls, Andy Warhol created his installation featuring repeating images to create his famed ‘Cow Wallpaper’. Until her exhibited piece featuring a couch covered with fabric phalluses – another signature feature of her work – Claes Oldenburg had never worked in soft sculpture. He went on to become famous for his creations in the field.

After creating the world’s first mirrored-room (an exhibit which led her to her Infinity Mirror Rooms), artist Lucas Samaras exhibited his own mirrored installation a few months later at a more prominent gallery – a complete change of direction for the artist. It was this that triggered one of several suicide attempts made in her life time, and moved her desire to create art away from the gallery setting.

She moved on to capture the hippie spirit of the late sixties in ‘happenings’, which took place at attention-grabbing locations such as the grounds of the MoMA, through to the New York Stock Exchange and the steps of the Statue of Liberty. She would paint the naked bodies of attendees with polka dots. In 1968 she staged New York’s first ever “homosexual wedding” including a wedding dress for two.

Whilst she staged these happenings with the desire of protesting for the goal of peace, she became associated with over-sexualised tabloid fodder, was heavily criticised by US media and subsequently scandalised in her home country of Japan. This cast great shame upon her conservative family.

Upon returning to Japan, she was bereft of support and subsequently attempted suicide again. With the return of her severe anxiety and hallucinations, she found solace in the mental hospital where she still resides, and slowly made her way back to her art that was her comfort and consolation. By all accounts, she continues to paint, draw, and create art for hours each day.

After years of becoming forgotten during her exile in Japan, her work was re-evaluated and her influence in the art world celebrated once again. In 1989, a retrospective of her work was exhibited at the Centre for International Contemporary Arts in New York. Her recognition in her home country was healed by her selection as the first solo artist to represent Japan at the 1993 Venice Biennale, supported by Japanese art historian, Akira Tatehata. It was a phenomenal success. Consequential exhibitions across the globe for her world-famous infinity rooms, polka dots and pumpkins, alongside an autobiography, ‘Infinity Net’ and a 2018 documentary, ‘Kusama: Infinity’ do justice to her title as one of the biggest-selling female artists in the world. In the kaleidoscope of her life and art, Yayoi Kusama’s journey is a testament to resilience, creativity, and the power of self-expression.